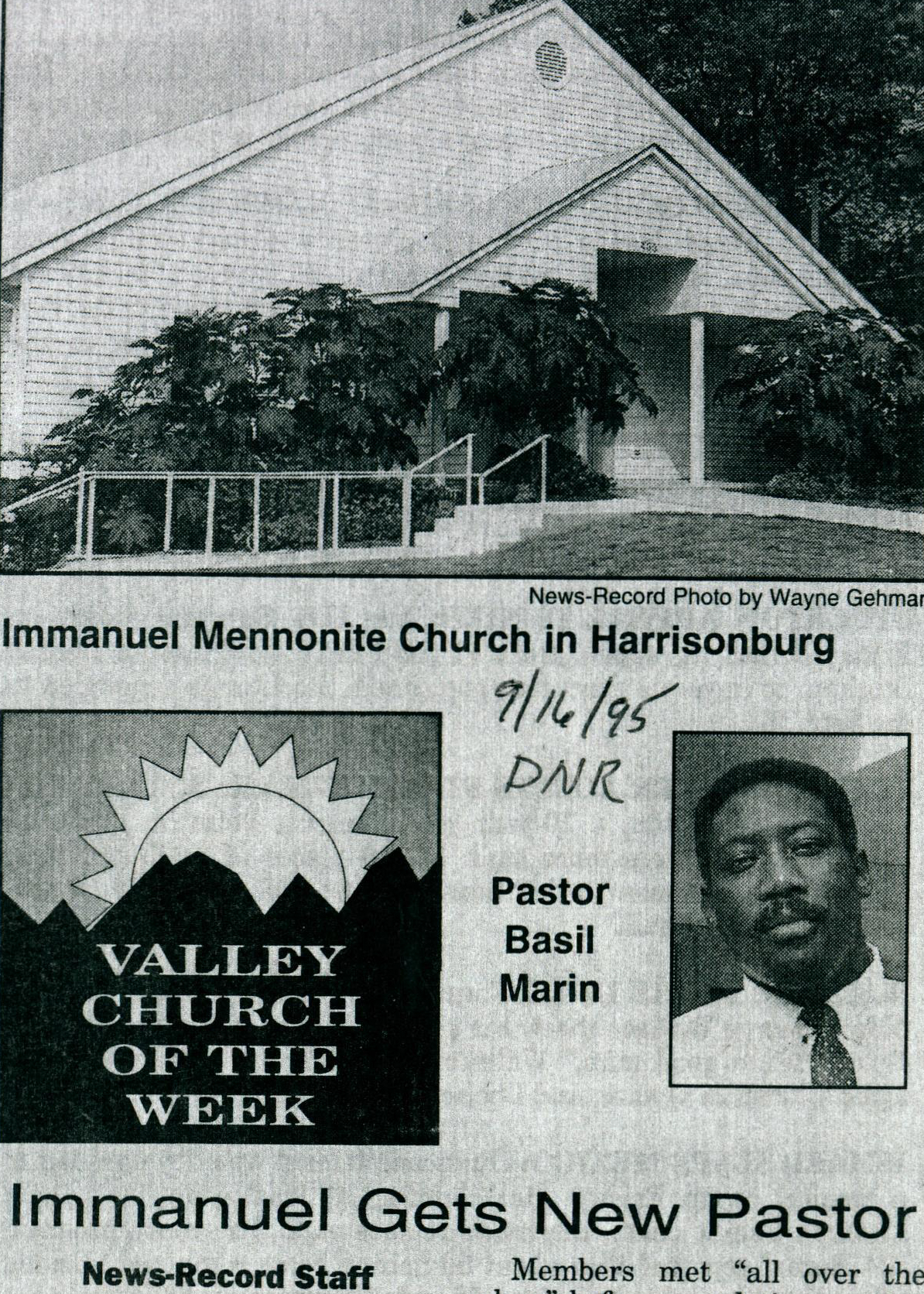

Both the past of the church and the land where it resides are full of changes. In the nearly 30 years since its founding, the church has been led by several different pastors and pastoral groups, experienced major fluctuations in congregation size and experienced the changing demographics of the neighborhood around them.

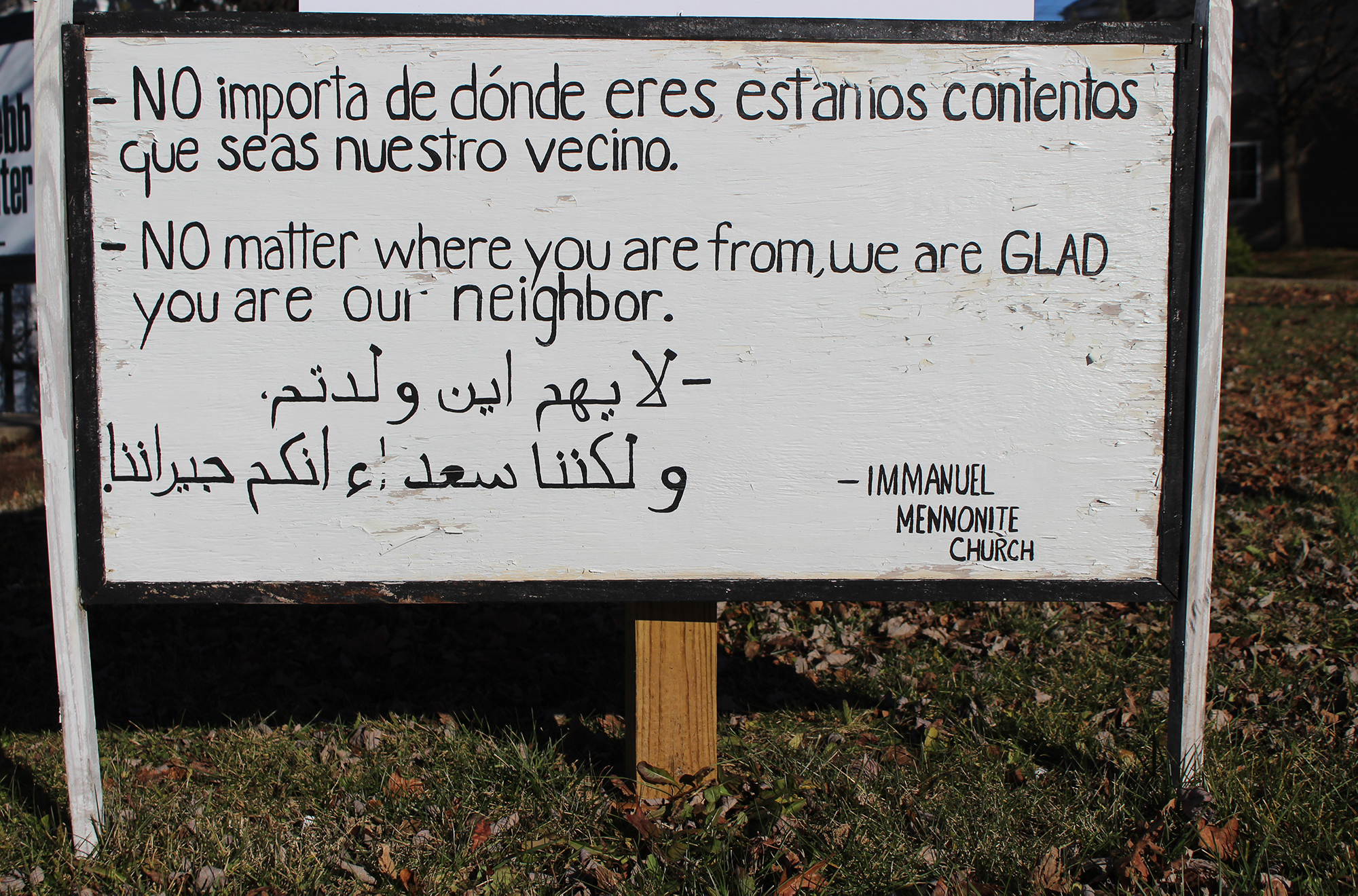

But the land where the church now resides has been marred by racial tension and inequality since the 1800s. The church intentionally chose this location with the goal of redeeming it. So, to fully appreciate the sign’s message of acceptance — both in terms of its meaning and its impact — it’s important to understand this backstory.

Using information from David Ehrenpreis’s book “Picturing Harrisonburg,” the congregation’s memories, community records, newspaper clippings, the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online (GAMEO) and census data we have provided a comprehensive timeline that stretches back more than 100 years before the church was established.

Early Days

A church that practices and preaches racial equality and acceptance sits on land with a

Robert Gray, a lawyer that Ehrenpreis says was “considered the wealthiest man in the county,” built Hilltop Farm. The Gray family, who actively supported the Union during the Civil War, owned as many as 17 slaves.

Formerly enslaved African-Americans from Rockingham and the surrounding counties gathered together and formed the community of Newtown, which stood on land formerly part of Hilltop Farm.

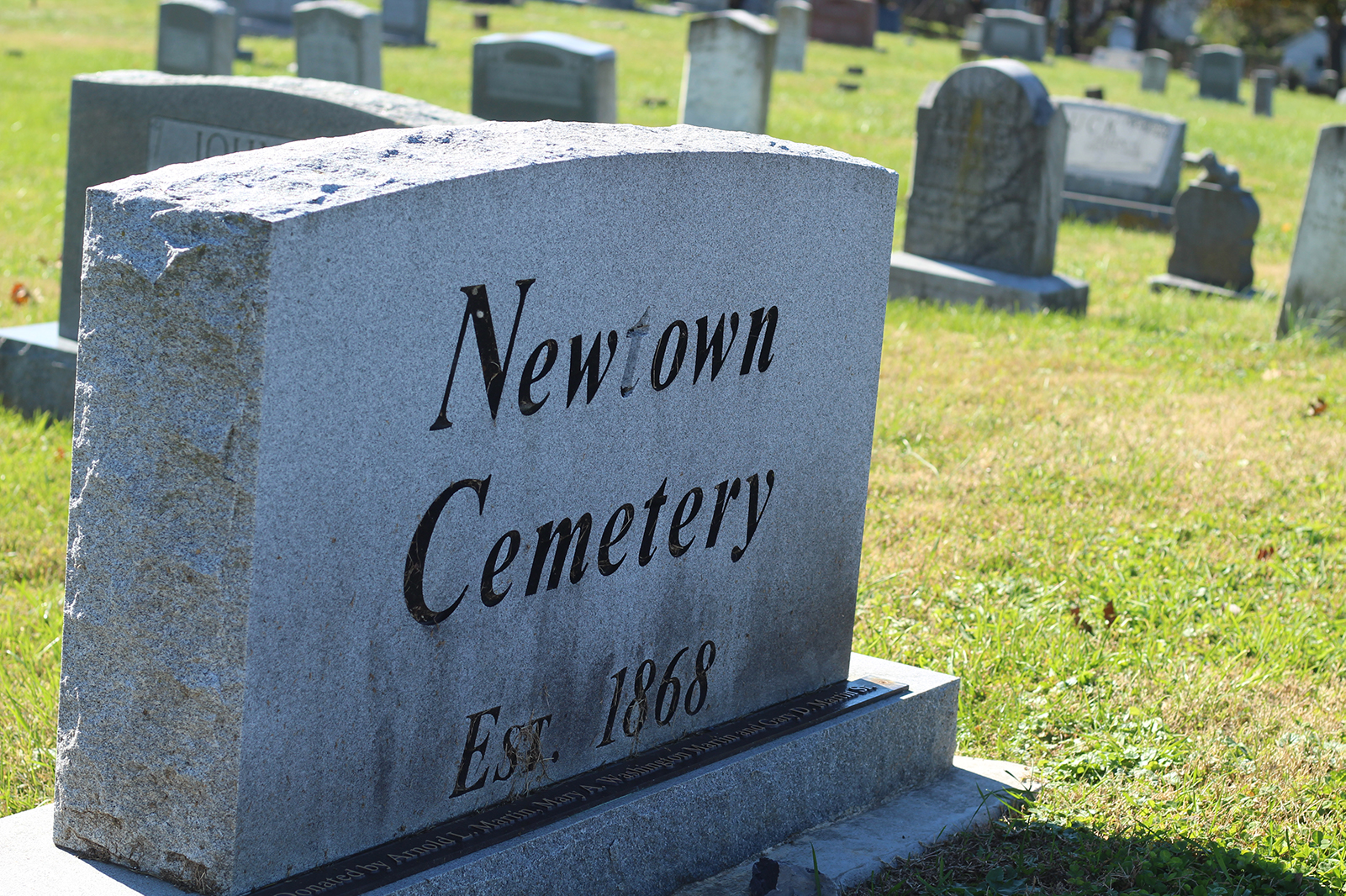

The Hilltop farm house burned down. Five men purchased three lots of the estate at the price of $250 a piece to establish Newtown Cemetery. The cemetery still stands today.